The fate of the Library of Alexandria is one of the history's greatest mysteries. For centuries, scholars have argued over who burned it, when, and why. As historian Roger S. Bagnall puts it, this is “a murder mystery with a number of suspects”, and no matter how much time passes, many still care deeply about it.

From the moment it was said to have been founded, the library represented an ideal: a place where all knowledge of the world could be collected, studied, and preserved. Yet, what we actually know about the library itself could fit on but a few papyrus scraps. The surviving evidence is fragmentary, contradictory, and often unreliable. For centuries, scholars, philosophers, and storytellers attempted to explain the gaps in knowledge of what we know about the greatest library of Egypt. This “wishful scholarship” has shaped the public understanding, producing a patchwork of conflicting stories that tell us more about the dream of the Alexandrian library than the actual place.

There is no ancient record describing when, how, or by whom the Library of Alexandria was founded. The earliest surviving mentions come from sources written hundreds of years after the supposed event. Among these is a twelfth-century Byzantine writer, John Tzetzes, who claimed that Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the second king of the Ptolemaic dynasty, founded the library with the help of three scholars: Alexandros of Aetolia, Lykophron of Chalkis, and Zenodotos of Ephesus. But Tzetzes was infamous for being “copious, quarrelsome, and careless,” his writings riddled with errors and self-aggrandizing.

The story becomes even murkier when another character enters the stage: Demetrios of Phaleron, an Athenian statesman and student of Aristotle, who fled to Egypt after a failed political career. Some accounts credit him with inspiring Ptolemy II to establish the library, but the timeline makes little sense: Demetrios served under Ptolemy I, the father of Ptolemy II, and died in internal exile long before the younger king’s reign.

An influential but dubious text, the Letter of Aristeas (second century BCE), complicates matters further. Purporting to be written by a courtier of Ptolemy II, it describes Demetrios advising the king to translate the Hebrew scriptures into Greek to enrich the royal library’s holdings. Modern scholars now regard this as untrue, yet for centuries, these claims were taken at face value, cementing Demetrios’s supposed role in the library’s story.

Unable to reconcile all the abovementioned contradictions, later scholars invented a compromise: perhaps Ptolemy I founded the library, and his son merely expanded it. This hybrid explanation survives largely because it is difficult to admit that there's simply not enough knowledge to speculate.

How Big Was the Library?

Ancient writers loved big numbers. Some claimed the library held 200,000 scrolls; others boasted 500,000 or even 700,000. Those figures have been repeated in textbooks and various documentaries ever since, but none of these numbers have a solid source or evidence.

Papyrus scrolls were expensive, fragile, and limited in capacity: each might contain a single play or treatise. To reach even the lower estimates, the Ptolemies would have needed to copy or purchase virtually every book in the Greek world, plus foreign works in translation. No contemporary evidence suggests such massive stockpiling of papyrus has occurred; it's more likely that these figures were inflated to emphasize the library’s grandeur.

Even if every known Greek author had left an extensive personal legacy (beyond the works that survived till our time), their complete works could not fill hundreds of thousands of scrolls. To reach those numbers, the library would have had to keep countless duplicates, drafts, and obscure texts, which is highly unlikely.

The truth is likely more modest. The library was enormous for its time, perhaps the largest collection of texts in the ancient world, but nothing like a modern research library. What made it exceptional was not its scale, however, but its academic ambitions.

A Death by a Thousand Cuts

Few stories in history invite more speculation than the destruction of Alexandrian Library. Akin to murder mystery, it has an array of suspects. Julius Caesar, during his Alexandrian campaign in 48 BCE, is often cast as the culprit; ancient sources claim his troops set fire to ships in the harbor, and the flames spread to nearby buildings. Some later chroniclers speculate that Caesar set the library ablaze on purpose, creating a kind of a political myth of the Roman conqueror orchestrating the destruction of the ancient knowledge. Yet Caesar’s own writings never mention such an incident, and the library seems to have survived well into the Roman period.

Other candidates for its demise include the emperor Aurelian, who sacked parts of Alexandria in the third century CE; the Christian mobs of the fourth century, accused of eradicating pagan learning; and the Arab conquest of 642 CE, when a much-later story claimed that Caliph Omar ordered the books to be burned. According to this later myth, in justifying the burning, Omar has uttered that “if they [books] agree with the Qur’an, they are superfluous; if they disagree, they are heretical.” This tale, however, is untrue: it was invented centuries after the fact.

A more likely explanation to the demise of the Alexandrian library is that is declined gradually over time. Wars, regime changes, earthquakes, and shifting cultural priorities all contributed to the library's neglect. Papyrus decays quickly without constant copying and care. As the Ptolemaic and later Roman governments lost interest in maintaining the library, funding dried up, scribes disappeared, and collections withered. By the time of the late empire, Alexandria’s great repository of knowledge may have simply rotted away.

What Was Truly Lost

For centuries, historians and poets have mourned the library’s fall as a humanitarian catastrophe, imagining that with it perished the wisdom of the ancient world. The image of flames devouring scrolls is of course, dramatic, but in the end, it's a romanticised symbol that doesn't carry much historical substance.

Yes, the library’s disappearance marked the end of a remarkable experiment in collecting and systematizing knowledge. That being said, the knowledge of the ancient world did not vanish overnight. Many key texts, from Homer to Aristotle, survived precisely because they were copied elsewhere: in Athens, Pergamon, and Rome. The greater loss was ideational: the Alexandrian library was believed to be a unique environment that brought scholars together to compare manuscripts, edit texts, and debate ideas.

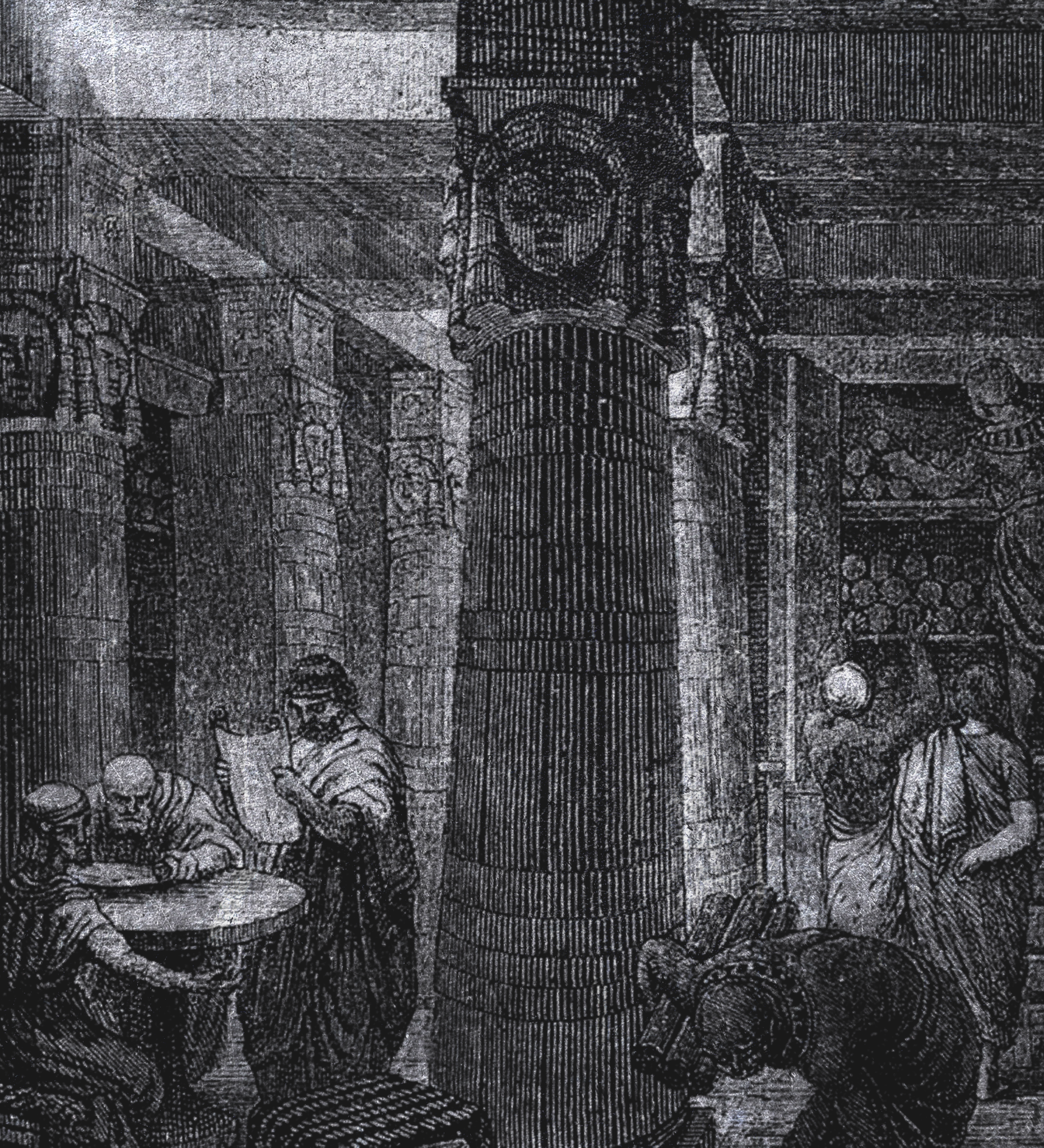

Alexandria’s library and its companion institute, the Mouseion, were described to function not just as archives but as research centers. Scholars there pioneered textual criticism, established canonical editions of authors like Homer, and advanced various scholarly fields from geography to medicine. This model of scholarly environments where knowledge is gathered, categorized, and analyzed, became the prototype for later libraries and universities.

Yet the dream of a perfect environment for scholarly exchange was way greater than what little we know about the physical site of the library. Each generation resurrected Alexandria as a metaphor: medieval Islamic scholars invoked it as a lost golden age of learning; Renaissance humanists saw it as a symbol of rediscovered wisdom; and today, the modern Bibliotheca Alexandrina that opened in 2002, stands as both an homage and rebirth of its ancient progenitor.

In the end, the Library of Alexandria exists more vividly in the imagination of scholars, writers and philosophers than in actual historical reality. Its significance, destruction, and legacy have been endlessly reinterpreted because they speak to unrealistic yet enduring human desire to gather and master all knowledge. Inseparable from human condition, myths and stories often arise from discomfort in the face of uncertainty. The less we understand, the more stories and explanations we invent. And in case of the Library of Alexandria, the dream of a perfect scholarly archive is so desirable and pervasive, that the myth of the library's grandeur and dramatic burning lives on through generations.